I wrote something for the ICRC about drones, public trust, and why we can't brute-force the public into being universally OK with the presence of little flying robots that are extremely hard to tell apart from one another. You can read it here.

Ever since that mind-bendingly awful heat wave hit the Pacific Northwest in late June, I’ve become obsessed with the history and politics of air conditioning. As part of my quest to become a minor-league expert on fun air conditioning facts, I picked up Salvatore Basile’s 2014 book, "Cool.” It’s a delightful wander through the history and cultural politics of air conditioning, and you should buy it.

In just the first few chapters, I learned:

For Europeans and Americans in the 1800s, people took the threat of cold extremely seriously. Heat, meanwhile, was considered a grim natural affliction that must be endured, often even unto death. As Basile writes:

"But when it came to a contraption that could cool the air - not only did many people not understand why it was necessary, but plenty of them scoffed at the notion that such a thing could even exist. Heat was a fact. Heat was a thing that heaven sent you. In those days, it was the Good Old Summertime. If the daily death reports told a different story, well, that was too bad." - p3

To this day, it seems to me that the West assigns uneven moral value to warming your house and cooling it down, despite the objective fact that heat waves kill a a whole lot of people. (Although most studies of the topic show that cold weather kills a lot more people than hot weather does, which was sort of validating for me as a passionate cold-weather hater).

In quite a few parts of the United States, air conditioning is still viewed as a bit of a soft luxury, or a way to deny the cruel realities of nature. As someone who was born in Florida, the Land of Air Conditioning, the Northeast’s skepticism has always alternately confused and amused me.

Meanwhile, very few people are willing to keep their house much cooler than 65 degrees in the dead of a grim Northeastern winter. Even the thriftiest and most themrostat-monitoring-obsessed Dad is unlikely to demand that the family keep the home at temperatures so cool that they can kill you.

Yet some Americans still try to shrug off temperatures so hot that they can be deadly. (Some of the vulnerable people who died in the 1995 Chicago heat wave, as Eric Klinenberg notes, had air conditioning units but simply never turned them on, probably out of fear that they couldn’t afford the expense of running them).

It’s funny how that works.

Pity John Gorrie. While working as a young doctor in the heart of Florida’s malaria country in the 1840s, Gorrie developed a revolutionary air-conditioning machine to help his fevered patients, which operated by compressing air to heat it up, then running that hot compressed air through metal pipes cooled with water.

Gorrie soon realized that his AC worked so well, it could even make ice, a marvelous boon in an era where most people had to special-order their ice from miserably cold places. Chief among these places were frozen-over ponds right where I live in the Cambridge, Massachusetts area, which served as the source for an entire global ice-block business. Gorrie was thus magnificiently well placed to, in the profoundly annoying parlance of 21st century tech, disrupt the ice business.

He applied for a patent by 1848 and got a mention in Scientific American in 1849. He dramatically demonstrated his invention at the French consul in Florida, serving people champagne on ice that he had made himself, right there in the swamp.

The future seemed bright. And yet, as Basile writes, Gorrie was most likely subjected to a remarkably comprehensive pressure campaign backed by Massachusetts ice-lord Frederic Tudor, who was not going to let his global ice-shipping empire be destroyed by some weird little swamp-dwelling putz and his horrible cooling machine.

Gorrie was labeled a “crank” who “thinks he make ice as good as God almighty” by the New York Daily Globe and had his financial backing pulled. A man who saw his machine and then talked about it back home in Georgia was expelled from his local church for lying, as it was “‘agin nature’ in the first place to make ice with steam.” He may have invented the world’s first dual air-conditioner and ice-machine, but Gorrie ultimately died a confused and disappointed man. We can assume that John Gorrie, for one, did not believe that the Market is Always Rational, or that the Best Products Always Win.

Keep this uninspiring little start-up technology story in your backpocket to irritate and anger any tech bro libertarians you may be forced to interact with.

In New York City in the 1880s, people were banned from sleeping in public parks during horribly steamy nights. Many slept on the roofs of their buildings instead. A surprisingly large number of people would regularly roll right off the roof and plunge to their deaths.

Death in the summer was viewed as weirdly inevitable back then, even more so than death from the various other things that could kill you quickly and unpleasantly befoe the modern hygiene era. Just like today, papers would print little whimsical editorials with little puns about The Dog Days of Summer, while also running a grim tally of deaths from heat exhaustion and heat injuries.

Sweatshops could hit 140 degrees, it was expected that ladies would swoon in church, and there was even an entire category of women’s summer furs. Doctors of the era were little help: they believed that suspect practices like “drinking water” and “removing some of your layers of woolen clothen” were dangerous practices during hot spells. Yikes.

A 1896 heat wave in New York City killed at least 1500 people, who were crammed into sweltering tenements. A then obscure police commissioner known as Theodore Roosevelt orchestrated giving away free ice to the poor of the Lower East Side, an experience that would set him on his political path to the White House.

There’s a common "well, AC made the American Southeast inhabitable" argument here in the US. I raise my eyebrow a bit when it comes up. It’s not that it’s wrong, not exactly. The advent of inexpensive home and office air conditioning almost certainly were key factors in the vast growth of the South and the desert cities of the Southwest after World War II. However. We should remember that indigenous Americans were living in these hot parts of the country quite comfortably before white colonizers arrived.

There’s this common American notion that people can only really do stuff with efficiency - build great cultures, erect edifices, have impressive wars, whatever - if they live in a nice temperate climate. Preferably one with four Northern-European style seasons that can be depicted in cute little Currier and Ives style knick-knacks.

But somehow India's great civilizations, the Khmer empire, and the enormous civilizations of the Amazon (among lots of other examples) managed to do all manner of impressive things in very steamy temperatures. And it’s also true that the depths of winter in cold and snowy climates weren’t, historically, a time of great productivity - at least before we developed better mechanisms for heating our homes.

This is not to say AC isn't, in the modern world, very important. It is! People in very hot climates die of heat-related conditions all the time, and horribly, those numbers are only rising due to climate change. But the implication that it was impossible for people to inhabit steamy climates before the invention of air conditioning is a bit much. People can manage to live almost everywhere: it’s just that before the rise of better ways to heat and cool our homes, a lot more of us died due to temperature fluctations than we used to.

As climate change ramps up, let’s work to ensure that we don’t return to those days.

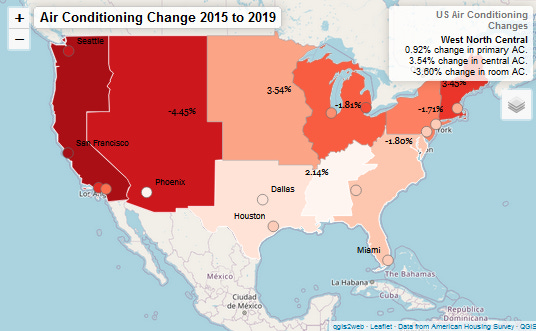

I made another interactive map of changes in US air conditioning rates between 2015 and 2019 for a class I’m taking. While the Pacific and the Northeast have historically been rather skeptical of the Demon Box that Makes the Cold, they're catching up fast. In Seattle, homes with some kind of AC increased by 10.27% between 2015 to 2019, while that rate has jumped by 7.46% in the Pacific region.

I'm writing a piece that will go into more detail on this.

Crustacean News

My partner got me a gigantic person-sized lobster pillow for my birthday. I can really suggest getting a gigantic person-sized lobster pillow to anyone who feels all lonely and alone in this cruel world.

My Twitter friends recently informed me of the existence of Evangelion toys in the shape of North American crawdads. A friend of mine who lives in Japan is helping me get them (they’ll be released in October) and I am endlessly grateful.

My friend Sina asked this question, though, and it’s haunting me. I can really see how you could make the argument either way.

That’s all I’ve got.

Faine Greenwood